Scented Thoughts: Perfume Symbolism in Liliana Cavani's The Night Porter {Movie Reviews & Musings}

The Night Porter (1973/74) was a very controversial movie at the time of its introduction and remains to this day. It is the story of the destructive and sado-masochistic relationship uniting a concentration camp survivor and her former Nazi torturer. The movie was based in part on interviews done by Liliana Cavani with concentration camp survivors.

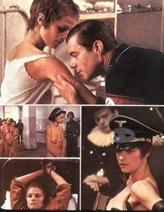

As the characters, played superbly by Charlotte Rampling and Dirk Bogarde, Lucia and Max, meet again in post-war Vienna 13 years later in 1957, the intensity of their relationship, to say the least, fully resurfaces, this time to demonstrate the impossibility of its continued existence and its doom. Lucia was 15 when she became Max's victim and lover and she seems to be irremediably marked by the experience.What had been limited to a game, paradoxically, when millions of people were being killed, notwithstanding the fact that it had been a dangerous and sickening one during the Nazi period, becomes suddenly something much more threatening. Max, who is trying to preserve himself from the new historical context by living like a "church mouse" in a hotel patronized by covert former Nazis, will not be able to fulfill his modest plan upon reconnecting with Lucia.The re-established rules of normal society now fail to be able to preserve their deviant behaviors and will even call for their condemnation by former Nazis who fear Lucia could stand as a witness against their crimes.

It is easy for someone external, like a spectator, to decide that Max is a deeply deranged individual whose pathology found expression and nourishment in the Nazi period and, were it real life, would have to be avoided at all costs. The problem of course is that looking at Max through the eyes of Lucia makes the situation much more ambiguous as it becomes quite evident that the former Nazi officer is able to have her experience an almost animalic joy and happiness that is best expressed by her strange, deep, and happy laughter punctuating her descent into oblivion. Undeniably, Lucia is happy, much more than she ever was with her conventionally handsome American husband who represents by contrast urbanity, culture, civilization and who happens to be a renowned music conductor. She may be, we suspect, at the center of Max's life in a way that she never was at the center of her husband's life...

It is in this context of perceiving the animalic and instinctive operate more powerfully than the rational and the civilized that, watching The Night Porter, one comes to notice that perfumes are showcased in at least three different scenes of the movie. Interestingly enough, these perfumes are not just present as mere decorative objects, as it sometimes happens, but are actively integrated in the exchanges between characters. After watching the movie (which I had actively avoided doing until now), I became interested in the reason behind these motifs and wondered why Cavani had decided to use perfumes in these scenes.

The perfume theme is by no means developed throughout the movie, although [spoiler] a sensitivity to bottle aesthetics is apparent even towards the end as a gracious glass oil decanter is shown in the background of the kitchen where Max is desperately searching for remnants of food in the trash to avoid starvation. The decanter is nearly full but the character does not think of drinking it for sustenance. It stands there like a souvenir of the outside world where food is easily available at neighborhood groceries.

The "perfume scenes" if you will are at the beginning and in the middle of the movie. Perfumes in Night Porter appear to be used to express ideas about sexuality, class, and inter-subjective relationship. Perfumes here, instead of elevating and idealizing the characters, making them appear more desirable and noble, are brought in to express not love, but prostitution, not attraction, but repulsion, not refinement but coarseness, not harmony, but destruction, not love, but a pathological manifestation of it.

It seems that Cavani uses fragrances as a symbolic means also for underlining the barriers and distance that exist between the different characters in the movie including an aging but still robust countess and her handy-man/gigolo, Adolph, and Max and Lucia. Despite the fact that these people come into contact and experience sexual intimacy, they do it in such a way as to stress their intrinsic strangeness to each other. For the countess and Adolph it is because their relationship is objectified by money, for Max and Lucia, it is because the nature of their relationship prevents it from being about an authentic communication and exchange of personal histories. We do not witness any conversation about their lives and interests outside of the S-M moments. We have no idea what their dreams, aspirations or childhood were. They appear to have no kin and are indeed portrayed as isolated, orphaned figures.They are forever playing out the same obsessive scenario attempting to recreate the dance with death that accompanied their relationship during the war. Max explains at one point that their story is a biblical one, that of Salome.

If we agree that perfumes, for the vast majority of people, are the choice receptacles of affective memory as well as symbols of attraction and seduction, then in The Night Porter this perception is altered. There is no affectivity linked to the scents in the movie, but rather deviant sexuality and this helps the spectator enter more and more into the perverse atmosphere of the movie as perfumes, as symbols, are turned upside down from being conventionally perceived as objects of illusion and beauty into objects that help reveal the absence of these in that particular universe.

The first scene in which perfume is staged is the scene taking place in Countess Stein's bedroom (played by a wonderful Isa Miranda) at the beginning of the movie where, although feeling a bit sick and unwell, the countess tries to seduce Max after he just subjected her to a gratuitous sadistic treatment, forcing her to take her medicine pills without water under the pretext that there is no more water to be had and overriding her fear of choking on them. Max declines her advances and instead suggests to her that it is time to call in "the usual assistance". At this, the Countess pulls away and looking wistful and accepting, starts toying with a perfume vaporizer that was lying by her side on the bed. She starts vaporizing the fur cover next to her with a jerking movement of the hand, looking a bit absent-minded, while proceeding in an habitual, almost automatic manner. Then she continues vaporizing the air around her in preparation for her lover and maybe also to express her frustration at the same time. In a way, the perfume both helps seal her rejection by Max and helps put her mind off the reality of Max's rejection.

Next is the scene where Max after having exited the countess' suite goes up to a small room under the roof to wake up "the usual assistance", that is Adolph, who also works at the hotel and who at first refuses to get out of bed in the middle of the night. Max harshly reminds him that he has received a month wages in advance at his own request and needs to honor his contract with the countess. This and his underpants thrown in his face after Max played ambiguously with them snapping violently and resoundingly their elastic finally determine the young man to change his mind. There follows a series of exchanges about smells and perfumes.

Max accuses Adolph of smelling bad and in particular of reeking of cheap mouthwash while the latter protests vigorously insisting that he actually wears an eau de cologne by Helena Rubinstein, described as being one for "men of distinction", this said with a defiant, roguish tone and a superb popular cockney accent. The young man then goes on to violently express his disgust for the perfume used by the countess (that she just sprayed on the bed covers while awaiting him) to the point that it makes him want to vomit.

We could see his reaction as a social protestation of sorts. He believes on one level that social distinction can be bought together with a cologne bottle and expressed by wearing it since this is what Helena Rubinstein's advertisement promises. This way, perfumes can nurture the illusion for the masses that they can all belong to the elite thus acting as an opiate for the people. Unfortunately for him, Max does not seem to share this illusion and thinks the young man is just smelly rather than fragrant. Max even plays in disbelief with one of the several bottles that he finds on the sink in the young man's garret. Since smelling bad can mean something more figurative than actually being stinky, perfumes or their absence thereof can mean in Max's language that Adolph is socially stinky by definition since he belongs to the masses. Viewed in this light, the young man's revolt at the thought of the countess' perfume can also mean something more symbolic and figurative. It can point at differences in class aesthetics, just like it can better than anything else express his instinctive disgust for the dominance of the countess or be seen as a vindictive action on his part; in other words, the masses may be smelly, but the truth is that a countess can be thought to be too.

Perfume here is further used to stress moral perversity, as it is not the act of prostitution itself that is made to feel ignoble to the spectator but something much less taxing morally, like an allergy to perfume. This movement that distracts the spectator's attention towards secondary details that become central helps to convey the marginality and perversity of the characters. It is echoed later in the movie by the flash-back scene where [spoiler] Lucia discovers that the gift presented to her by Max after her half-naked dance in a Nazi uniform is the head of a prisoner who was annoying her. The camera concentrates on Max's expression of delight and excitement akin to that of a child opening his Christmas presents as he watches Lucia on the verge of betraying her disgust and fear with a gag reflex. The problem in that movie, as I see it, is that people want to vomit but nobody ends up throwing up either for major or secondary reasons so that the game goes on. The spectator experiences also a similar state of mind and continues to watch a movie that is made to feel disgusting enough but not completely unbearable.

The addition of this more articulate second perfume scene where fragrances are again mentioned and a series of bottles on a sink shown, calls one's attention back to the meaning of the first perfume scene with the Countess. The Countess may be using the perfume herself to cover up the traditional stink of the working class or to make herself more desirable or to put a veil of scented illusion and beauty (for her) on an act that is essentially crude. The irony, of course, is that her perfuming gesture provokes the reverse of what is intended. But perhaps, she does not think so much of the young man as of herself and of her nerves that need to be calmed down. Cavani plays on the traditional ambiguity of perfumes which may be perceived very differently by different persons, either become objects of attraction or repulsion. Because perfumes intrinsically do possess this ambiguity and ambivalence about them, it becomes, at yet another level, an efficient support for expressing the ambivalence of the characters and the lack of moral landmarks.

The third scenes in which perfumes are staged is one taking place in the middle of the movie in Max's bathroom in his apartment in town. Lucia playfully escapes Max's embrace at one point and rushes to the bathroom closing the door behind her. In a stroke of inspiration she takes one of the beautiful perfumes bottles found in the bathroom and smashes it to the floor. At this point Max succeeds in opening the door, steps in, and press down unknowingly with his naked feet on the pieces of glass scattered in a pool of perfume. He winces only ever so slightly, Lucia looks proudly at him as she has just demonstrated her sexual creativity; ensues a moment of silent appreciation for both. When fascinated by the blood trickling down Max's foot, she puts her hand in a caressing gesture under his arched foot, he brings another twist to the game by pressing down with it on her hand which in its turn gets cut by the shards.

In this scene, perfume bottles with their balanced, classical formal beauty and connotation of civilization serve to negate such characteristics as being obviously desirable for everyone. Where the spectator's eye is pleasingly attracted towards a line of three fancy perfume bottles, each with a juice colored in different bright colors, the spell is soon broken by Lucia as she uses one of them to make it participate in the economy of her distorted relationship. Why choose perfume, again, to express such distortions? Perhaps, Cavani, playing with the sense of perfume consumerism of the spectator, knows that she will strike a chord by destroying an object that is a focus for feelings of luxury, beauty, sensuality, and seduction, especially as seen in the hands of a woman. Lucia could open one of the flacons and dab some perfume on her to, as is more traditional, attract her mate, but in this case, she knows that the scent, while bringing some pleasure, won't secure as much pleasure as in the transgressive way in which she uses it. She could have seized a glass with a toothbrush in it, but it would not have called as much attention on the negativity and perversity of the act; who really cares about a simple drinking glass? She could have rushed to the bathroom with a bottle of wine in her hand and smashed it on the floor and although the blood symbolism, the beauty, and the sensuality could have been connoted by the spilled wine, it would not contain a reference to seduction, sexuality, and aesthetic beauty in the way that perfumes can.

The incongruity and inversion of the references made to perfumes in The Night Porter is doubly incongruous in that this rarely takes place in movies. To call upon the spectator's sense and experience of smell rather than vision to help portray the lines of tension and complexities of the characters with some consistency is not common. Especially so as perfumes here are not conventionally portrayed as ideal objects of desire and beauty. In line with their real personalities, perfumes contain both elements of the primitive, instinctive and the aspirational and ideal, things that are echoed well in the semiotic use that is made of them. Seeing Cavani bringing in the culture and symbolism of perfumes reveals another original facet of the movie.

Now, a guessing game. We can try to imagine what perfume the countess might have been using and wonder how Adolph was supposed to smell as well as ask ourselves what perfumes an ex Nazi officer like Max might have been keeping in fancy silver and crystal bottles in his bathroom.

Thank you for digging this movie out of the vault, Helene, and giving us such an insight into the use of perfume in it.

Now it will one day make it onto my TV screen via a rental so that I can witness these images of perfume as a silent, yet sensed, ingredient in the filmmakers bag of tricks. Amazing social and political commentary on the iconic status of perfume and scent in society.

Hi Anya,

Thank you. Although this movie was regularly featured in my neighborhood when I was living in Paris, I did not muster the courage to watch it until now. I knew it would be difficult to take it in and it is.

I hope that you will find it interesting if not likeable.

What a perceptive reading of The Night Porter... I had to do a short article on it recently for a book I'm writing which is a cultural encyclopaedia of sex (there's also an article about perfume, of course). After so many years, it's still hard to find the right words to capture this movie, isn't it? But it remains a beautifully dark, distrubing film about erotic passion...

Oh boy! You got me first and used the pic (the top one) I had been meaning to use all along in my own blog...maybe I will still use it,though, LOL

This is one of my favourite films for many years and it must have made an impression on you!

I don't think anyone who wants to really catch perfume shots has anything much to expect, but indeed the idea of bourgeois luxury that perfume usually represents is shattered in a film that shatters the concept of tameness and happiness in a quiet, arranged life, just like you say so well.

A superb film! Thanks for reminding us.

Hi Carmencanada,

Do let us know when the book is out, we could advertise it since perfume and sex are intimately related:)

I watched the movie only once (but twice the perfume scenes) and I prefer to leave it at that for the moment being; I prefer to remain a bit external to the movie.

It is a very complex movie when you start thinking about it and definetely disturbing, as much because of what it shows as because of what it does not show; ethically, I feel a bit disturbed by the fact that the issue of Nazism retreats in the background to focus more on the erotic passion itself. A difficult movie it is indeed.

Hi Helg,

I'm sorry to be source of disappointment for you:) It's indeed a nice picture and you should do as you think is best:)

The movie did make a strong impression on me. I prefer not to be too sympathetic to the characters and hence will not watch it again soon.

I was struck by the perfume scenes more the first time I saw them. The second time, I perceived them less intensely so it might have been a question of greater focus and attention the first time I discovered the film.

Anyone interested in this film might like to take a look at http://www.lilianacavani.com/

I never liked Cavani. She seems to delight in portraying the worst in everything. Maybe that's why "critics" like her so much (no offense to you, MH; I found your review quite brilliant). I remember another film by her (the name escapes me at the moment), also dealing with Nazism (sp?). This one was about Nazi occupation of Italy. A disturbing and rather disagreeable film. "Night Porter" ("Portiere di Notte," in Italian) is another example of "Cavani art." But what do I know? I'm just what some would call a "bourgeois Philistine." Still, I have to admit that MH draws attention to a very interesting point about perfumes in the film.

Cavani or rather her movies are not easy to "like" and obviously not meant to as there is so much provocation and a primal stomach-churning factor in them, but at the same time she does tackle difficult topics. There is the Berlin Affair which takes place in a Nazi context...

Ah, yes. What would we all do without these "artists" provoking us into facing reality (rolleyes)? I mean, we could read History, of course. Then again, neither Charlotte Rampling, nor, say, Angelina Jolie play any of the main roles, so it's all very boring, really. Whatever. Nothing personal, MH, you understand. It's just that I don't like some "artists."