'Round Midnight Poison by Dior {Scented Thoughts}

The rose-patchouli-amber accord was particularly popular in 2007 in women's perfumes although it is fair to say that it has always been popular. If a competitive exam topic had been handed down from the skies to the perfumers' community asking them to come up with their own rendition of this accord, it would not have felt any different. To some extent, it all goes back to the agricultural roots of the trade. Just like one might visit an annual agricultural exhibition where the best Camemberts and Charolaises from France are shown and compared, one might be standing in front of shelves with perfumes such as Gucci by Gucci, YSL Elle, Dior Midnight Poison on them and see who got the gold medal of excellence. It is perfectly respectable that perfumes be about the refining of a traditional idea. In this case, originality is partial, and like good perfumes, subtle. Or if you prefer a more palatable comparison brought about by the thought association between Midnight Poison and 'Round Midnight and the idea of circularity, it is like a jazz standard that would be interpreted each time in different, personal, and creative ways.....

This phenomenon invites us, once more, to reconsider the naive proposition that perfumery is geared towards the production of unique works of art, works that should never be repeated. Setting aside the problem of recognizing the mass-market aspect of most perfumes and the dominance of a few huge perfume corporations which homogenizes perfume production -- a problem that was studied by Eric Schlosser for food in Fast-Food Nation - one can turn towards the problem of the constant iteration of the ideal of the unique perfume as reflective of one's unique essence. This is not an idea that one imposes on hamburgers and fries, or at least to a much lesser extent. You might prefer Burger King over McDonald's or hate both, but it is not about "you", but more about external food preferences and ideals of food quality. In other words, chances are you will feel more detached towards a hamburger than towards a perfume you are going to wear.

This highly idealized representation is based on a fundamental confusion between a dominant invidualistic ideology where perfumes are concerned, which makes the wearer wish to express his or her uniqueness through perfume-wearing, and the conditions of creation in perfumery, and one might add art in general. To think that a work of art is a one-shot proposition contradicts the experience that art is about deepening, exploration, variation, obsession etc. If anyone is tempted to put the constraint of uniqueness on perfume seen as non-repeatable art, it is according to the fallacy that a perfume exists to make you feel unique, distinctive and espouse all of your contours. As Elisabeth de Feydeau reminds us in Une histoire mondiale du parfum, the idea that the perfume reflects the person is a modern evolution and originates in the French court society where "le paraître" is all important.

If we start de-constructing perfume, we realize that the very notion of "sillage" is all about personal identity. It is a trace of oneself that one leaves in a room after having departed from it, or that announces one even before entering it. It is a form of palpable charisma. It is scented medieval banner with your colors trailing behind you in the wind.

If a scent and personality association might have started more simply with an aromatic being linked to a particular individual like neroli with Anne Marie Orsini Princess of Nerola and jasmine with Madame de Maintenon up until the turn of the 20th century where women were associated each with their own soliflores, it has come to develop into a full-fledged quest for the "I" in perfume, even to the point of promoting an ideal of wearing a unique scent marker for life. In this eminently egocentric or narcissistic vision of perfume that is only interested in or constantly seeking the "me" in perfumes, the quest, if it goes on, can probably only lead to frustration or momentary satisfaction at best if one puts too much emphasis on the work the perfume must perform to meet one's ideal representations of oneself. In a more realistic approach, the perfume will not be that drastically different from others, but will be a part of one's sense of style, drama, and as congruent with the moment.

One can also decide to look at perfumes as expressions of the craft of the perfumers who create the perfumes and in this case, one is bound to notice that perfumers think more along the lines of briefs or raw materials or anything, but you. At best, a type of woman or man will be described in the brief and you might incidentally feel affinities with the perfumery interpretation of this idea and the beautiful publicity imagery that creates in you the desire to identify with the perfume.

But really, perfumes follow their own logic, especially if they are works of art more than commercial productions. The very people who bemoan the "repetitiveness" found in the works of Lutens or Ellena ought to realize that it is a sign of artistic integrity and the result of the exploration of personal ideas. The balance that perfumers have to strike between commercialism and art, wearability and sheer originality is delicate, but a commercialized perfume is never about "you" first and foremost and does not need to be "unique" to qualify as a great perfume. The same thing can be said for art. In other cases we are obviously confronted with near-mechanical copies but the nose and the eye can tell the difference. Without going into the question of who the "I" is over time, it appears problematic to believe readily in a perfume that is a mirror of one's personality, even if layered with others. At most, you will learn to adapt to the perfume(s), not the reverse.

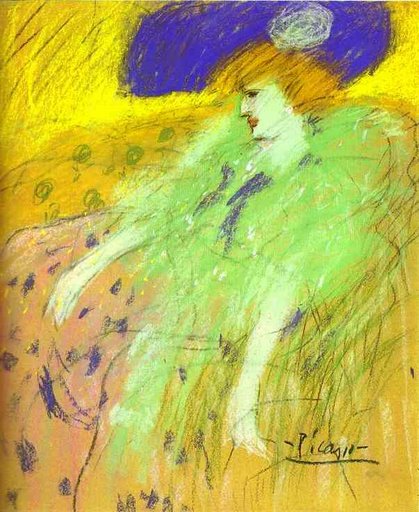

Images: picassaweb, lentos.at, es.easyart.com

I often "interview" the people I meet through my job about their perfume: there is indeed a category that identifies very deeply with their chosen scent --never mind that it's usually Shalimar, which brings us to the paradox of adopting a mass-produced identity!

I agree that many parfumeurs-créateurs, when granted a relative freedom, will work on variations and refinements of the same basic ideas. You named Lutens and Ellena: I could add Roudnitska, who, apart from Diorissimo, a specific commission from Christian Dior, basically redid the same scent all his life.

Now the reason you state for wearing perfume to enter a perfumer's world rather than to express one's identity is precisely the reason why I wouldn't get a bespoke perfume even if I could afford it: it's so much better to be taken where you didn't expect to go, than to spell out the destination.

But then again, coming back to what I've found out through my "interviews", most people just buy something they quite like, change when the flacon is empty and don't look any further.

Dear Denyse,

Thank you for your comment.

I think that the phenomenon "perfume" is not just about the perfume itself. It is about our relationship to it, the images, words, personalities that surround it. This is one of the reasons why I so enjoy perfumes; they are an infinitely complex phenomenon.

Considering perfumes are works of artists is yet another perspective one can bring to the study of perfume and sometimes it applies well, at other times, it's probably irrelevant to think of certain products in these terms.

Roudnitska is a great reference as far as perfumer-artists go. He is one who has the most consistently thought about what he was doing.

I think that a bespoke fragrance can have different levels of originality. In many cases, it will make use of pre-existing accords that are well-known to the perfumer.

Yes, it is good to remind everyone that blogs offer a somewhat biased view of perfume habits. "Normal" people do not do genealogical comparisons for example and will be perfectly happy to discover a good fragrance that just smells great on its own.