Le Guide du Parfum by Rebecca Veuillet-Gallot: Book Review {Scented Thoughts} {Fragrant Reading}

We wanted to do a review of it because we almost bypassed it in favor of more copious tomes not expecting to find a tremendous amount of information in the rather slim copy. Once we started reading it, we had to realize that underneath its understated character, it is a wonderfully rich little book that one will go back to, finding new details each time depending on the questions you ask yourself.......

There exist several perfume guides, which no doubt for practical reasons, develop the genre of the short perfume description. Susan Irvine, Nigel Groom, Luca Turin, Jan Moran come to mind whose books are still in the relatively easy-to-find circuit (there will be a new Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez guide coming out in April of 2008). But there are others as well, which are however not as systematically based on fragrance reviews and are more general historical and practical guides (they are quite numerous in French).

Rebecca Veuillet-Gallot’s style is that of a connoisseur aided by the insider’s insights of a professional perfumer, Jeannine Mongin, who now officiates at L’Osmothèque. Although Amazon.fr offers the information that the author is a junior artisan perfumer, her reviews feel educated, but not rooted in her profession. She offers balanced judgments, which sometimes clearly reveal her own subjective preferences, but never in a dogmatic fashion. For example, she really does not like L’Eau d’Issey and states so explaining that she has to move away each time she smells it on someone as it evokes to her “an impression of oyster tray accompanied with apricots that I find particularly unappetizing!”. But she remains open enough to suggest other perfumes in that new-freshness group, which she dislikes intensely. She has no political agenda that one can sense, such as pushing products or perfumers she has befriended, except for her love of perfume inherited from her mother and grand-mother. She easily recognizes that her favorite family of perfumes is the oriental one and this part of the guide is thicker.

The book is divided into the 7 fragrance families used by the Association Française des Parfumeurs. These divisions have been criticized briefly for example by perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena in his Que-Sais-Je.

One thing is certain from the perspective of one who writes daily about perfume such as yours truly is that fragrance families overlap more and more in so-called pluralist perfumes and new sub-families are created seemingly every month. But from a practical standpoint, it is perfectly acceptable to choose to divide a perfume guide this way.

One may adhere or not to the underlying theory of taste it postulates, namely that each individual has a deep preference for a unique family of fragrances. Perhaps so. Perhaps there is only one type of perfume family we would marry and feel happy with while gallivanting with others, but it might also be a worthwhile effort to separate love of perfume with love of self and just try to appreciate perfume in a more aesthetically detached way by thinking about them as surprising (or snooze-worthy) encounters with different minds, sensitivities, and outlooks. After all, when visiting the Louvre and stationing yourself in front of the Joconde, you don't necessarily ask the question, "Is it me?". Nor would you if you went to the farmer's market and smelled each kind of tomato before deciding on the ripest and most flavorful ones.

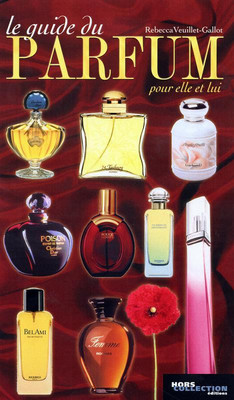

The book selects about 200 noteworthy perfumes. Its philosophy is very much indexed upon the premise that perfume is a personality and style enhancer. Veuillet-Gallot even offers advice on how to best dress with each perfume.

The short perfume review genre is an exercise in evocative brevity that one is tempted to liken to the art of the sketch in drawing where one has to render a visual impression with a few, well-chosen tracings of the pencil. It is an economical and synthetic genre, which hopefully gives a fair idea of the fragrance talked-about. But perhaps more importantly for many a perfume aficionado, it gives them the wish and the curiosity to explore further the rich and transient world of perfume.

One of the ways that this desire of exploration is created is for example by drawing historical or intuitive links between fragrances that up until then one thought had no connections between them. For example, Veuillet-Gallot explains that Guerlain L’Heure Bleue and Gucci Eau de Parfum are linked (but she does not mention Coty L’Origan, factually documented by Michael Edwards and in which the connection is often felt). Or that Shiseido Féminité du Bois is the mother of four Serge Lutens Palais Royal perfumes (Bois & Fruits, Bois de Violette, Bois Oriental, Bois et Musc) at the time Lutens needed to set up a library of perfumes, as well as of Dolce Vita by Dior later on.

Perfumes are often intimately connected between themselves for different reasons that have to do with perfumery being a craft producing personal care items. It is also a creative art, less often.

The guide by Rebecca Veuillet-Gallot may appear a bit unassuming at first with its modest proportions and lack of hubris. For example, she fortunately avoids over-simplifying jingle statements such as “let me proclaim here that this is the best perfume in the world and that’s that” or alternatively “since the dawn of humanity” or “the pinkest of all perfume ever, I swear” etc. that feel like suddenly a Barnum circus is in town trying to sell you a ticket to go see the smallest midget on earth.

Her reviews are rarely downright critical although she is less diplomatic than Jan Moran, but aim more to bring elements to better enjoy perfumes in their historical and cultural context. For example, Mitsouko was Jean Harlow’s signature perfume and the author mentions three of her films in which the perfume appears on a dresser: Red Headed Woman (1932), Dinner at Eight (1933), and Riffraff (1935). She likes to see a link between Boudoir and Agent Provocateur created by mother Vivienne Westwood and son Joseph Corre. She points out that Estée is sometimes called “Super Estée” and she analyzes it as a “ floral perfume with a French signature but with the powerful effect of an American perfume”. Trésor is reported to be called by Sophia Grojsman “Câline-Moi” (cuddle me). Or Musc Ravageur smells of the musk used in the great Guerlain perfumes at the turn of the 20th century. Information about synthetic molecules is offered.

The author deplores the derelict direction in which perfumery is headed. She writes that “The decline of perfumery started around 1985-1990…” evolving from a craft to an industry where “Time is money”. Although one cannot deny the higher and often crass marketing pressures put on perfumery, a situation bemoaned by many people, as well as the loss of quality oftentimes, the fact remains that it seems to us that perfumery is progressing as well.

The new perfume compositions offer a sophisticated structure that make older formulations look like kids’ drawings. There are plays on spatial volumes in perfume that are very interesting. The palette of the perfumer has expanded considerably offering more diversity and opportunity for perfumers to develop a personal signature (Alberto Morillas and Jean-Claude Ellena are reported to stick to about 200 raw materials). There are just too many beautiful perfumes in the world to experience them all as they should be.

Since the reviews in this guide-book are short, they might be understood by Anglophone readers who are already aware of perfume terminology and have a good dictionary. It is certainly a worthwhile read. From an American standpoint especially, it will probably not contain enough information about so-called “niche perfumes” of the more confidential variety (On the other hand it constitutes an interesting European perspective on fragrances.) But her style of writing is enjoyable to read, the information she gives is interesting, her “sketches” are a sensualist’s pleasure, and her book is valuable for what one is tempted to call her “wisdom”: her personal voice, her independence of mind and efforts at objectivity; she even tries to objectify her "goût et dégoûts" (likings and distates). It feels “old money” but as applied to perfume.

The book is priced at 18, 05 €.

What we lack now is a really good book about how to appreciate perfumes. I came across several books devoted to tea or cofee, very well written (in French and English) with really great topics on how to smell/taste discover the different flavours - books speaking about flavour itself and the pleasure that comes with, and not focused on brands or a specific commercial product.

I'd love to read something like that on perfumes, not about history&brands but more focused on the particular smells and how to better appreciate some perfumes and maybe (re)discover other fragrances we were not aware.

I see what you mean. I was thinking about the topic on how to best smell/appreciate a perfume. I wonder how far this could go though without referring to branded perfumes?

I was thinking more on switching the accent from brand's history (and perfume history) on the smell itself or other things. Let's say ... to really appreciate a great perfume like Femme maybe there would be other things to smell before (like cumin, Rumeur Lanvin, rose absolute, Mitsouko, etc). Because in the end, when you wear it, it's not a label that you put on (like in fashion) but only a smell. I also reflect on that, maybe I will write something.

I think that an important difference with tea, coffee, and wine books of that nature is that the connoisseur feels connected more to nature by inhaling these aromas and tasting them. It is interesting to smell aromachemicals, but you do not feel that kind of connection, except through a reconstruction of memories.

I see you tend to cite natural raw materials.

But yes, I absolutely agree that more emphasis has to be put on aesthetic, sensual, and learned appreciation of scents instead of immediately thinking of perfume as a beauty accessory and a personality-enhancer as I said in my review. This is why picturing yourself smelling tomatoes and asking yourself the "Is-it-me?" question is funny, to me. The sense of taste/smell directed towards vegetables and fruits is devoid of the primary narcissism inscribed in the perfume culture.

It is so impoverishing to think of perfumes as mere extensions of the self -- big yawn here.

I think that L'ABCdaire du parfum by Georges Vindry, Nicolas Martin de Barry, and Maïté Turonnet is a little bit more along the line of what you are thinking of, at least with their accents on raw materials. I know that for Maïté Turonnet the raw-material angle is critical.

I appreciate the well thought-out book review and would like to elaborate on one point. Indeed, a scent formulation is a work of art like a painting, which should not be viewed solely from the perspective of whether one would like it hanging in one's living room...... However, if a scent formulation is to be used as a perfume, I believe that it is valid to view it in the same way that we view the art of architecture, in which we recognize the merger of form and function as one of its artistic objectives. I see two different arts, scent and perfume, and with respect to the latter, the sniffer may ask not just whether it yields insights or beauty, but whether it is a creation that she(he) wants to live in (i.e., whether its decorative, self-expressive, enhancement or other functions are gratifying)....... It does not necessarily flow from this that a perfume must be superficial, pretty or boring. A profound scent may be a wonderful perfume. Still, I wanted to note the validity of two different sets of objectives on the parts of both artist and sniffer.

I also think that one should approach perfume in a supple fashion.

What makes it a truly wonderful phenomenon, is that it is so complex, especially if you have the time to play with time. It then takes on still further layers of meaning.

J ai lu le livre de Mlle Rebecca Veuillet Gallot, il a ete traduit en roumain et j l ai beaucoup apprecie parce qu il est ecrit par un createur de parfums qui s y connait bien. C est un livre tres captivant et charmant.

J aime enormement les parfums. mon histoire d amour pour les parfums est triste et gaie, commique et dramatique, dramatique parce que j ai depense beaucoup d argent sans trouver le parfum que j aime, comique et dramatique si je me rappelle la douleur que j ai sentie quand on ne voulait pas me devoiler le nom d un parfum que j admirais enormement. Je pourais ecrire enormement sur mes rencontres heureuses et malheureuses avec les parfums. je voudrais enormement travailler dans le domaine de la parfumerie, je ne sais quoi, dans une grande maison importatrice de parfums de tout le monde, par exemple. si quelqu un lit ses lignes et peut m offrir un pareil emploi, je vous prie de m ecrire a l adresse adriana.funaru@yahoo.com.

merci beaucoup