Nomad Two Worlds Raw Spirit Fire Tree {Perfume Review & Musings} {Green Fragrances}

Fire Tree Fragrance Oil by Nomad Two Worlds

Fire Tree is the debut scent by Australian non-profit Nomad Two Worlds founded by photographer James Russell and spearheaded by CEO Joyce Lanigan who was instrumental in turning the project into a business. Launched in 2012, the fragrance oil has led to a Raw Spirit collection of further perfume collaborations with native, indigenous communities, and is now available at Harvey Nichols alongside the others. Having personally gone back to smelling more natural perfumes if only just because they are now more abundant in the market led by lifestyle choosers, I decided to review Fire Tree as one of the options to consider but also to better gauge the aesthetics of today's natural perfumery...

Let me preface this review by stating that « Natural » is a tricky term because although it sounds like a label, it is mostly an unregulated metaphor. More recent natural scents list ingredients, their provenance and the proportion of naturals vs. Synthetics while specifying the percentage of « organic », eco-certified ingredients. The house specify that,

« This fragrance oil has been created using wild-harvested raw material collected with consent and collaboration of representatives of the Nyoongar people of Western Australia, the traditional Indigenous guardians of the Fire Tree. »

On the face of it, Fire Tree is a potent, herbaly potion - a blend of medicinal plants. It smells apothecary-like. It reminds me of a deodorant I like to use, Weleda déodorant à la Rose, which is all-natural and ancient-smelling as far as the way its rose scent translates to the contemporary nose. This deodorant I use in part because it makes me think of ancient 18th century perfumery, Marie-Antoinette's Little Trianon and Le Sillage de la Reine perfumer Francis Kurkdjian made based on an ancient Versailles recipe. You can smell this kind of ancient rose smell sometimes in Lush products too.

Past these initial impressions, a woodier facet emerges featuring Australian sandalwood but also the Fire Tree extract. The overall sensation can be described as being creamy, salty, mineral-y, but also rubbery, which might be my idiosyncratic translation of the smokiness which is advertized ; it smells faintly of burnt tires.

Shades of Serge Lutens Santal de Mysore come into focus with its kitchen-like nuances of spicy Indian curry stew. In the depth of the accord, there are hints of green, of coolness and freshness and a breezy floralcy, which do not feel as much rehearsed.

For me, it is this undercurrent of freshness which « makes » the scent, making it stand out a bit. It smells almost minty, but not quite. You can however register a tactile impression of mentholated coolness which washes over you although the scent of « mint » is barely forming as such. Given the philosophy of Nomad Two Worlds which is to select culturally meaningful notes for its blends, this could be a dash of Eucalyptus oil dispensing its coolness like portable air conditioning for the skin; but it could also be Cajeput oil as it smells very similar to that aromatic profile in fact. Cajeput is a native plant of Australia, found in its hottest zones.

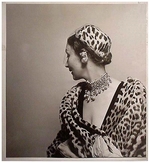

© James Russell

Past this camphoraceous, turpentine grove moment discreetly exhaling inside the trunk of the Fire Tree struck open by lightening, the perfume turns caramely, sweet, and cake-stand like. There is a pyramid of vanilla-frosted cupcakes sitting on the stand and when you bite into one of these, you notice the liberal pinch of salt the baker added. It creates an edible sensation.

Curiously then for an authentically sourced perfume from one of the Australian terroirs, there is a connection to the global gourmand trend smelling uniformely of Maltol. The lack of strangeness in the sweet accord is a let-down if you look to Fire Tree hoping to smell the Outback prior to the industrial revolution, with at most a note of wild honey. Why pre-format such so-called indigenous scents ?

Granted, this might be an idealized view of traditional communities. In reality, modern life is accessible to all and willingly accessed. Who are we to decide that an Outback-inspired perfume cannot smell of a Coca-Cola note ? There is danger in essentializing cultures, and olfactory cultures at that. Let 's decide to let the winds of perfume flow freely around the globe.

The fragrance was composed by a global fragrance supply and composition company, Firmenich, and Harry Fremont in particular. Even though Tasmanian oils were sourced and a genuine interest in local Australian scents was expressed, « sweet » smells like what your current idea of sweet in perfumes smells like. I already saw that trend in natural perfumery with an American eco scent smelling heavily of Maltol, which is by itself an organic, naturally occurring compound.

Perhaps it's high time to refine this sweet concept to escape the limited range of sensations running along the notes of white/burnt sugar, salty/sweet caramel, light/heavy syrup and white/black vanilla. Perhaps it is because we think of sweetness as that of white caster sugar mostly that, like for the color white, which has become associated with non-color in modern times, a sweet base in perfume can smell bland. This effort has to be made on both sides : the emitter's and the receptor's sides. Perfumers must cultivate their olfactory language and we, our reading skills.